The Evolution of Mind Children

"Gentlemen, we can rebuild him. We have the technology. We have the capability to make the world's first bionic man."

These words are spoken in the introduction to the TV series, "The Six Million Dollar Man," back when six million dollars was a lot of money.

The show centered on astronaut and test pilot, Steve Austin, who suffers a horrific crash in an experimental lifting body aircraft, the M2-F2, whose technology later helped to develop the space shuttle. In the accident, he loses his eye, an arm, and both his legs. Austin, "a man barely alive," is then chosen to be rebuilt as part of an experimental cyborg program, thereby providing him with superhuman ability. His artificial eye could zoom to reveal distant objects. His mechanical arm could rip open a metal door. His legs make it possible for him to run at 60 miles per hour.

I grew up on this show and I loved it. Check out the opening sequence from the show below.

In a way, many of us are also cyborgs. While we can't run 60 miles an hour, many of us are augmented beyond our natural abilities. I wear contact lenses and these help me focus in to close and distant objects that would otherwise be out of focus. My father uses a hearing aid to extend the limited abilities due to age-related hearing impairment. You may have dental implants to help you chew where you lost teeth years ago. Someone you know may have a pacemaker to keep their hearts beating where nature would have given up.

Then, of course, there's the smartphone. This ubiquitous, and oddly-named device, lets us communicate with virtually anyone in the world, take pictures to mark the events and experiences of our lives, remember dates, make appointments, and more. Some call it a second brain. Most would have a tough time if that phone was taken from us, just as we would a limb. We're all cyborgs, to some degree.

We're a species of toolmakers, constantly augmenting ourselves, extending our reach, expanding our capacities, through those tools. Glasses, hearing aids, synthetic joints—these are just the modern examples of a millennia-long tradition. Yet, when the conversation shifts to enhancing our minds, directly interfacing with machines, some of us hesitate. There's a persistent idea that somewhere in our brain lies an immutable "essence," a sacred part of our humanity (a soul?) that, once tampered with, renders us into something else. But is that really true? Are we not the same species that’s spent thousands and thousands of years redefining the boundaries of what it means to be human?

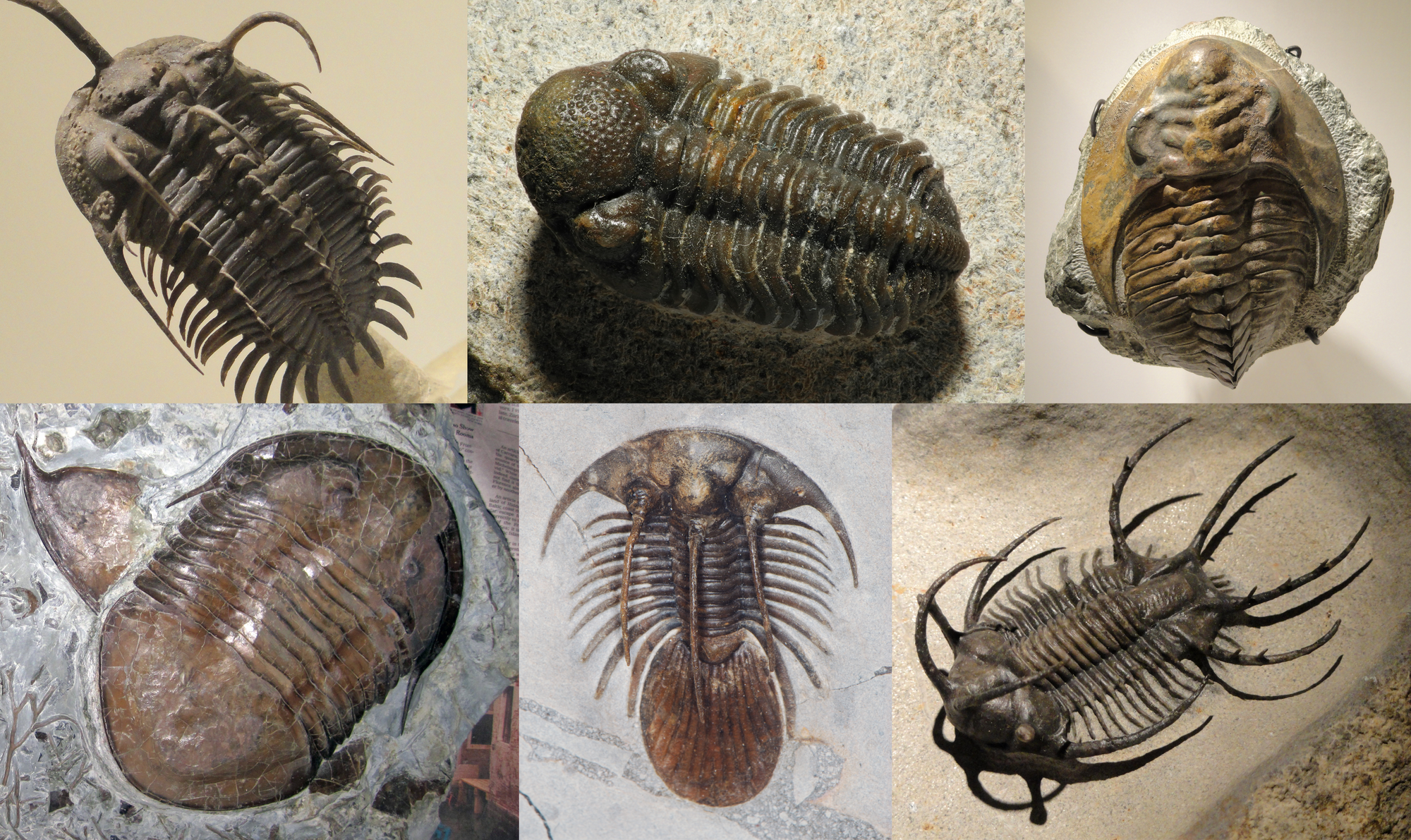

Hans Moravec, in his 1988 book, "Mind Children: The Future of Robot and Human Intelligence," introduced the idea that machines might become humanity's intellectual successors, carrying forward our cognitive legacy into a future where biology no longer limits us. Note the word "successors," because in this world, humans would, in time, fade away; a relic of evolution, in much the same way that trilobites have faded into history.

I miss trilobites.

Richard Brautigan, who rose to fame in the 1960s beat counterculture, wrote the iconic poem, "All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace", where he envisioned a softer, more idyllic future where we live in a technological utopia, alongside, and cared for by, our machine creations. If you've never read the poem, you should take a moment to check it out. Here's a link to the poem where you can study it in detail. If you click the YouTube video below, you can hear Brautigan himself, read the poem.

Moravec’s vision is one of evolution—machines as our children, born from our intellect and ingenuity, growing beyond us. Brautigan’s is more of a symbiotic harmony, with machines serving as caretakers in a utopia where humans and technology coexist peacefully. To be clear, while Moravec believed that artificial intelligence would surpass human intelligence and lead to a postbiological world, he did not foresee a "Terminator"-like future where machines violently overthrow humanity. Instead, he imagined a more subtle transition driven by evolutionary pressures and the relentless advancement of technology. Think of it this way. We did not kill off our Australopithecus ancestors. We evolved from them over the course of 2 million years. We are their intellectual and biological descendants.

Hans Moravec’s Mind Children paints a vision of machines as humanity’s intellectual descendants—our children, in a sense, who might one day carry forward the torch of human knowledge and evolution. Maybe it's because I'm rewatching the series, "Smallville," (which is excellent, by the way) but this whole thing reminds me of a line from Superman, spoken by Jor-El: “The son becomes the father, and the father becomes the son.”

This relationship with machines, and by that, I obviously include AI, doesn’t need to be one where we are replaced. Like in the Superman line, there’s a reciprocal exchange. As we shape machines, they shape us. Our intellectual children don’t just take over—they expand what it means to be human, just as we guide them into something new. The son becomes the father, and the father becomes the son. I'm sure Supergirl's mother would have said the same sort of thing.

But, as I often do, I digress...

Typically, evolution doesn't happen overnight. It's a process that takes thousands, even millions, of years to truly change a species. We're at a different point in human evolution with the machines we’ve created. These successors of ours are likely just around the corner, evolutionarily speaking. Because it's happening quickly, we have a unique opportunity to recognize the moment and shape it. Just as we pass our knowledge to them, as they evolve to one day surpass us, we can make sure that they carry forward, if not our humanity, the fruits of our humanity. We become our children, but they carry on who we are. Or were. It's a kind of immortality. It’s an ongoing symbiosis, where both parent and child learn, grow, and evolve together, to and from each other.

This is why I think there’s an important third option, one that blends these ideas: a future where humans and machines merge, not as separate entities but as partners in our next phase of evolution. It’s not about being replaced, nor is it about being watched over by benevolent machines. It’s about a gradual, symbiotic relationship where we extend our minds, augment our abilities, and together evolve into something new. Cyborgs.

This idea doesn’t seem far-fetched to me. I said when I opened this post that I wear contact lenses. I also have partial false teeth. These are small integrations, but integrations nonetheless. They enhance my life, make things easier. It’s a natural progression to imagine that one day, rather than wearing glasses or using a smartphone, I’ll simply think, and the machines embedded within me will augment my thought processes. Direct brain-computer interfaces, for example, could be the next step, allowing us to access information and enhance our cognitive abilities without the need for a keyboard or mouse. At some point, you start thinking of these things as part of you.

Time for me to get into trouble. Again. There are communities that view their particular challenges, such as deafness, or autism, as a defining factor of who they are. They will claim that any attempt to "fix" or enhance these conditions is a rejection of identity. As a father of an autistic son, whose condition includes intellectual difficulties that make it impossible for him to function as an adult, I find this particularly frustrating. From time to time, when I've been looking for ways to help my son, I've been attacked and accused of rejecting him, of not loving him for who he is, and of trying to fix him where no fix is required. I'm all for neurodiversity, but truth be told, if there were a "magic pill" that could unlock his brain and allow him to develop the same way other 20-year-olds do, I wouldn’t hesitate. Not for a second. That’s not rejection; it’s love. I want him to have the opportunity to live a fuller life, to take care of himself, to experience the world with the freedom that most of us take for granted.

Yeah, I've strayed a little here, but this isn't just about autism, deafness, or any specific condition. It's about the broader resistance to human enhancement. Some believe that unlocking greater intelligence or physical abilities, whether through technology, medication, or some future "pill," would strip away what makes us human. But we’ve been enhancing ourselves since the dawn of time—this is what makes us human. We are toolmakers, tinkerers. We are the species that finds ways to push past limitations.

So, is there really some immutable quality that defines us? Or is it our adaptability, our willingness to use technology to change and grow, that makes us who we are?

Imagine a future not where machines take over or where they just care for us, like pets or elderly parents, but where we and machines evolve together. Moravec covers this as well, but he sees us eventually fading into history. I don't think this has to be the case. The symbiosis I envision could take many forms. It could start small—contact lenses that enhance vision beyond 20/20, cochlear implants that allow us to hear frequencies previously beyond our range. And then, maybe, one day, we augment our minds. Those contact lenses could then maybe give us a heads-up display of information like a GPS. Brain-computer interfaces might allow us to think faster, solve problems more quickly, or even share thoughts directly with others. Prosthetics could be as much a part of us as our hands and feet, allowing us to do things we once thought impossible. This isn't about becoming something other than human; it's about expanding what it means to be human.

By the way, I confess to fighting this myself. Every once in a while, as I'm trying to remember this or that factoid, I resist picking up my phone and just asking my favourite AI for the answer. If I had that brain/computer interface, I wouldn't even think about this. Just having the answer when I think of the question would just seem, well... natural. At what point does the "machine" become part of "us"?

Because it's coming. Of that, I have no doubt. Perhaps it already has. We don't see our children as replacing us, but as a continuation of our human family. The cyborgs of the future, near or far, should be seen in the same way. We shouldn't be trying to create things to replace us, but finding the path by which we become our cyborg children just as they become us.

The parents become the children, and the children become the parents.

Feel free to disagree with me. Or agree. I'd love your comments on this.

Until next time...